Analysis

The environmental cost of the War on Tigray

Published

5 years agoon

It has been more than six months since the Ethiopian regime of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, the 2019 Nobel Peace Laureate, declared a full-scale war on the Tigray region, one of the member states of the Federation. Despite initial claims by the regime that it is a “law enforcement operation” of minimal impact on civilians, reports now reveal that the impacts of the war on civilians and the region in general are unprecedented. Multiple reports indicate that farms, industries, homes, hospitals, schools and other civilian infrastructures throughout the region have to a large degree been looted and destroyed by Eritrean and Ethiopian armies as well as ethnic militia from the neighbouring Amhara region loyal to Mr. Abiy Ahmed Ali’s regime. Tens of thousands of civilians have reportedly been killed.

So far, over 60,000 civilians from Tigray have crossed the border to seek refuge in Sudan. Millions of others are reportedly internally displaced within Tigray as war rages across the region despite claims by the federal government that the “operation” has ended following the capture of Mekelle, Tigray’s capital, on the 28th of November, 2020. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), there may be upwards of 1.7 million internally displaced people and about 4.5 million face starvation.

Tigray and the wider Northern Ethiopia region are historically prone to droughts and dry spells. People in the region are, as a result, highly vulnerable to food shortages due to their almost exclusive dependence on small-scale agriculture. During the last 50 years alone, there have been three major famines, which resulted in deaths of hundreds of thousands of people. The 1973 famine in Wollo, Tigray and Eritrea (part of Ethiopia at the time) led to the death of over a million people and to the eventual overthrow of Emperor Haileselassie, the ruler of Ethiopia at the time. Another and an even more calamitous famine, at least in Tigray, was the 1984/5 famine. This was due to a combination of natural and human made disasters. On the one hand, the vulnerability of the region to droughts and the impacts of sporadic weather conditions is partly a result of environmental degradation due to a long history of farming on very mountainous landscapes. Droughts in the years leading up to 1984 left farmers with little or no grain in their stores. On the other hand, in addition to the continuous droughts, the Derg or Mengistu Hailemariam’s regime was at war with the region making it difficult for Tigrayans to obtain food stocks from the market even if they had the money to do so. Moreover, the war impacted farmers, as their homes and farms were constantly attacked by Mengistu’s army in retaliation to their alleged support for the rebels. In many cases, entire villages had to be rebuilt after devastating arsons and bombings by the Ethiopian army.

The struggle in the 1970s and 80s was thus as much against environmental calamities as it was for the liberation of Tigray from Mengistu Hailemariam’s military dictatorship. A clear indicator of this focus on the environment is the level of emphasis that the government of Tigray region and civic organizations such as Relief Society of Tigray gave to environmental rehabilitation both during the war, in the liberated areas, and following the end of the war in 1991 in the rest of the region. After the war, both the regional government and civil society organizations such as Relief Society of Tigray focused on linking relief, rehabilitation and environmental protection in their rural development programs. Tigrayans volunteered 20 days a year to participate in organized environmental rehabilitation works.

According to the Chris Reij, a researcher with the World Resources Institute in Washington whom The Guardian interviewed in 2014,

“The scale of restoration of degraded land in Tigray is possibly unmatched anywhere else in the world. The people … may have moved more earth and stone [in recent years] to reshape the surface of their land than the Egyptians during thousands of years to build the pyramids,”

Chris Reij

The result of the efforts of this scale is that Tigray has in the last 30 years achieved remarkable progress in terms of regreening and restoring its degraded mountainous landscape and improvement of the living conditions of farmers across the region. The once poverty-stricken region became a symbol of change, restoration and improvement of the life conditions of its population as the impacts of droughts on the livelihoods of farmers were significantly reduced.

Thirty-five years after haunting images of crying, skeletal Ethiopian children shocked the world, Tigray, the region that unwittingly became a poster child for famine, is taking on a new image – that of resilience.

(Reuters, 2019)

Through decades of carefully coordinated effort, the region has been able to demonstrate that restoration of degraded landscapes is possible. In 2017, Tigray won gold in a UN-backed award for “the world’s best policies to combat desertification and improve fertility of drylands.” The transformation was more dramatic in some villages such as Abraha We-Atsbeha, which we now hear has become a battleground. Through community-based restoration efforts, the village was transformed from once on the brink of resettlement, due to degradation and resulting deteriorating living conditions, to winning the UNDP’s 2012 global Equator Prize for successfully “restoring degraded land” and significantly improving the lives of its residents. There are plenty of similar success stories across Tigray.

The war on Tigray, I am afraid, may reverse most of the progress that was made in the last 30 years. While the environmental impact of the actual war itself, i.e. the pollution effect due to the logistics of the war and physical destruction, is undoubtedly huge, the focus of this article is on how the war may affect the relation between the people and their environment. So, how does the war affect Tigray’s environment?

Internal displacements & temporality of living arrangements

Nearly a third of Tigray’s population is currently internally displaced, which means without any external support people are living in caves and in remote mountains burning anything they can find for cooking, heating and everything else. The impact of internal displacement on the environment, and vegetation cover in particular cannot thus be overestimated.

The deployment of troops by warring parties on the environment.

In addition to the displacement of civilians and rise in the demand for fuelwood, warring parties – Ethiopian and Eritrean national armies, Amhara ethnic militia and various regional armed groups loyal to Abiy Ahmed Ali’s regime on the one hand and the Tigrayan Defence Forces (TDF) on the other – have deployed hundreds of thousands of troops in Tigray since the start of the war. Feeding these massive numbers of troops for over six months requires a significant amount of energy supply. In the absence of electric power supply and no formal market for fuelwood, troops would have to depend on local resources. The presence of troop movement of such a scale may have colossal impact on the forest resources of the region.

Damages on civilian infrastructure and increasing poverty:

The damage on civilian infrustructures due to the war are of industrial scale and systemic. Power supply lines, schools, health facilities, homes, factories and farms and so on have been looted and systematically destroyed. Most of the region, including big cities, has been cut off from power supply for almost 6 months and may continue to be so. Lack of access to electric power means that millions of Tigrayans who previously depended on electric power have to use firewood and charcoal for cooking and heating across cities and towns. I fear this may reverse a promising regreening effort of the last 30 years.

Moreover, living conditions for many households may not be the same even if the war ends soon. Many will have lost their jobs in factories and other businesses, which have either been looted and destroyed during the war. This will leave many unemployed and poorer than they were before the war, and there is a higher possibility of them returning to rural living as it is not so long ago that they moved into cities. Reverse migration, i.e. urban-rural migration, may lead to additional demand on land for farming and the extraction of resources in rural areas.

Destruction of homes, farms and public buildings

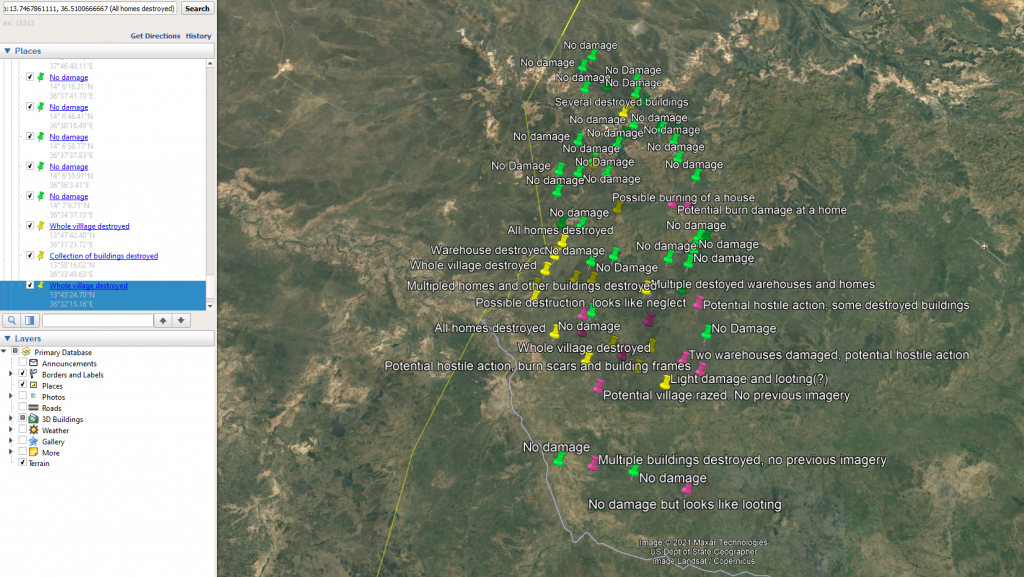

In many cases, villages have become battlegrounds, which means civilians and their properties are often caught in the crossfires. Many villages have been shelled by heavy artillery, drones and war planes. Multiple reports and satellite images show evidence of complete destruction of villages and towns across Tigray. In other cases, from what we hear from some people who managed to get to major towns in the region, to gain access to phone connections, the invading Ethiopian and Eritrean armies and ethnic Amhara militia loyal to Abiy Ahmed Ali’s regime have destroyed farmers’ homes in retaliation for defeats in battlefields. Entire villages are in many cases looted and destroyed by the invading armies. Multiple reports indicate deliberate burning of houses in villages. According to Reuters, 500 buildings were burned down in mid-February 2021 around the small town of Gijet, 60 Kilometres south of Mekelle, the capital city of Tigray, in what seems to have been intentional arson by the Ethiopian army. Similarly, in Cheli village of southern Tigray, the Ethiopian army torched an entire village in retaliation for a defeat in a battle against the Tigray regional forces.

In Fredashum, a sub-district of Gulomekheda in Eastern Tigray, local sources reported that over 595 homes of farmers, schools, shops and a health post were burned down by Eritrean troops. Similar reports of houses burned down are reported in Kilte Awalaelo, Atsbi Wenberta, Samre and many other places in Tigray.

Burned down house in Samre

A burned-down Tigrayan homestead, allegedly in Atsbi Wenberta

Farmer Hagos stands inside his house which was burned down by Eritrean troops

Adi Mendi village of central Tigray near the border with Eritrea has been turned into a “ghost town” as Eritrean soldiers razed 478 housing structures to the ground; that is literally every farmer’s home in the village along with everything the farmers owned. Many farmers were also “burnt alive” inside their homes.

The destruction is even worse in Western Tigray, where satellite images show entire villages across the sub-region that have been destroyed by ethnic Amhara militia that now occupy the area. Check the Twitter thread here for comparative satellite images of destroyed villages in western Tigray.

In addition to the fires detected within the Hitsats ref. camp, 3 other detected fires in North Western #Tigray felt within settlements within the last 48 hours; in the attached map, fires within settlements are drawn with an explosion sign, other fires outside are smaller dots. pic.twitter.com/ktJty1U0mW

— FIRIS – Fire in Settlement (@FIRIS_FireAlert) January 7, 2021

The environmental impact of such destruction is not difficult to imagine. Tigrayan farmhouses are mostly built from stones, wood and mud, i.e. stone walls with a combination of wood and mud roofs. Destruction of homes in villages at the scale that is being reported means that these houses will have to be rebuilt when the war ends, if it ends that is. Reconstruction will in turn mean that there will be overwhelming demand for logs. As there is no formal market for logs anymore, farmers may have to depend on trees that they can access in their areas. There is no doubt that this will reverse the significant progress that has been made in terms of regreening Tigray’s landscape. It took Tigray over 30 years of intensive effort to rehabilitate tree cover, which is now in danger of relapsing.

The targeted destruction of irrigated farms

As part of the environmental restoration efforts, the government of Tigray and its development partners invested in a wide range of small-scale irrigation schemes which benefited farmers and helped in regreening eroded flood plains. These schemes have reportedly been significantly impacted by the war.

According to a report by the Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development of the interim administration of Tigray, 10% of small-scale public irrigation infrastructures and more than 90% of irrigations infrustructures by private investors have been systematically destroyed. The report also reveals that more than 70% of seedling production stations that supplied Tigray’s fruit gardens, reforestation programs and livestock feed for farmers have been looted and destroyed bringing replanting efforts in the region to a near complete halt.

Eritrean troops and ethnic militia from the neighbouring Amhara region destroyed fruit gardens and plantations in many parts of Tigray. To give an example of the extent of damage, a report by the interim administration indicates that over 22000 fruit trees covering about 850 hectares of irrigated land were destroyed by the invading armies in the district of Samre of the Southeastern Zone of Tigray. Similarly, the report revealed over 3000 fruit trees covering 35 hectares of land in Degu’a Tembien district within the same zone have been destroyed by Eritrean soldiers. The destruction is reportedly even much more widespread in areas bordering Eritrea and the Amhara region to the south of Tigray.

Locust invasion

During the weeks prior to the start of the war, Tigrayan farmers were battling against one of the worst locust invasions in recent history without any external help as the Ethiopian federal government had suspended any support to and cooperation with the region. Locust swarms commonly affect all kinds of vegetation both in farmland and in the wider landscape. When the war started, the battle against locust swarms came to a complete halt as villages became battlegrounds and families had to run for their lives. The effect of this is that farmers have encountered loss of significant portions of their harvest. But it also means that without the measures by the farmers, desert locust swarms were left unabated to consume the rest of the vegetation; pastures and forests. As one local contact said, “locusts swarms have been left free to eat everything.” The impact of this on the wider environment cannot be overstated.

Impact on protected areas

Before the war, Tigray had one of the most organized environmental management systems in the country. The structure ranged from village level councils to regional bureaus responsible for the restoration and protection of the environment. With the overthrow of the formal elected government and its formal structures following the war, the environmental management and protection system has entirely collapsed. This may have grave implications on protected areas and the wider care for the environment. According to Abadi Girmay, head of the Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development of the Tigray’s interim administration, the war has immensely impacted years of environmental rehabilitation and protection efforts. He said;

Environmental protection and restoration that we invested on for over 40 years and for which we have won global prizes has now been completely reversed. Areas that were restored and showed good progress are now burning, forests cut down and converted into charcoal. We are not all able to save these. [….] This will cost us another 50 years to recover from. We could not even pay the salaries of rangers. Most of our seedling stations

Abadi Girmay

Tigray’s precious protected areas are heavily impacted by the war. The Kafta-Sheraro national park, which is home to the northernmost elephant population in Eastern Africa and a wide diversity of unique wildlife is in grave conditions as Eritrean forces now occupy the area where the park is located and its management system has collapsed. With the collapse of the park management system and formal government in the region, precious wildlife and the park in general are left for plunder and destruction. Protected areas such as Higumbirda, Girat-Kahsu and Dese’a forest reserves, some of Tigray’s last remaining mountain forests and home to a diverse wild species have also become active battlegrounds. According to the Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development of the interim administration, protected areas in the region have become battlegrounds, their legal basis eroded and their guardians disarmed leaving these areas exposed to overgrazing and deforestation.

The environmental cost of the war on Tigray is undoubtedly immense. While it may appear like a luxury to talk and write about the environmental cost of a war when the lives of millions are at stake, it is precisely for this reason that we need to talk about it. In a context of war, the priorities of people shift towards short-term concerns and the environment is not one of them. Life decisions focus on surviving today as tomorrow is uncertain and invisible. The war on Tigray is thus as much an environmental disaster as it is a political and humanitarian crisis.

Tekehaymanot G. Weldemichel has a Ph.D. in Human Geography from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. His research focuses on environmental policies and politics. He is currently a postdoctoral research fellow at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology where he studies the translation of the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into policies and practices.

Eri Embeba

May 9, 2021 at 9:37 am

In his latest interview with Abbay Media, former Ethiopian Prime Minister Tamrat Layne says the party that Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed leads under the guise of Prosperity Party has become like Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF).

Mekete tigray is composed of eritreans and do defend the release of eritreans and amhara POWs for political gain. Eritrean accent can save your life and they donot mind of you kill Tigreans .Tigrean conspiracy theorists are justifying the release of POWS and killing Tegarus is like killing a spider for them. And they find it avoidable and they cannot be questioned by any legal entity for killing Tegaru. So, they donot care for Tigreans in Tigray but they do worry for amhar and Eritrean detaineees.Do release everyone including socalled Banda, Tigrean origin if you release Eritrean killers and amhara generals. We asked you to bring to justce but not releasing them to kill mothers and sisters!Hypocrite Leaders!Why did you fail to consider the worst scenario if you believe you know everything and can do everything moretahn any one ?Humanity is liable to imperfection regardless of its civilization and level of education and authority .

You are taking about eritrean ecape while people are massacred in your own land and dying from hunger!Money making outlet.

He was specific that Oromo Democratic Party which emerged as a dominant force within the Prosperity Party the way TPLF was a dominant force during Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF).

mekete tigray agregate of hypocrites and children of ex-political elites