In-depth

Western Tigray: A Tigrayan Territory Since Antiquity

Published

3 years agoon

By: Negasi Awetehey

1. Do Not Make the Indisputable Disputable

Amhara´s expansionists have claimed that “Tigray annexed lands from Amhara.” This invalid, unconstitutional and politically motivated accusation has been used to commit ethnic cleansing of Tigrayans in Western Tigray with the potential support of the Ethiopian regime and the invading State of Eritrea. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, in November 15, 2022, addressed his parliament using “Welkait“ an unconstitutional expression itself that makes the indisputable Western Tigray unfairly disputable. With his blessings the joint forces are still undertaking the ethnic cleansing, and changing demography, built environment, social landscape, and language.

After the promulgation of the federal system in Ethiopia in 1991 which also formed an ahistorical Amhara map, some disgruntled Amhara politicians and People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) operatives stood against it. Slowly, Amhara and Eritrea, which sees Tigray’s existence as a political entity as a mortal threat, waged propaganda campaigns fabricating stories, such as Welkait as Amhara land, Badme as Eritrean land, and more. To make up their narrative, the expansionists use, abuse, misquote, and omit historical facts and evidence; no one has scrutinized them. Achamyeleh Tamiru´s fictitious text which meant, “Welkait has never been administered by Tigray“ is a perfect example that intentionally ignores numerous historical maps and the work of the renowned scholar Richard Pankhurst (1990) that mentions “Wälqayt in Tegré.”

In this article, I will show that Western Tigray, both in history and in identity, has and is part and parcel of Tigray, but first some background history.

2. Tigray: Antiquity, Development and People

Archeological sites and written sources in Tigray demonstrate a rich, continuous history of polities. The emergence of organized societies gave rise to polities known as Punt (2500 BC) and Da´amat (1000 BC- 400 BC), which were precursors to the Aksumite polity (100 BC-800 AD).

Tigray’s history can be conceived in three main phases, the first covering the period of antiquity up to the 19th century (hereafter: Historic Tigray); the second, from the 19th century until the fall of the Derg in 1991 (Provincial Tigray); and the third, spanning the era of the federation, in which Tigray has been a semi-autonomous member state since 1991 (Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, EPRDF´s Tigray).

Inhabiting the strategic position of the Horn of Africa, the people of Tigray have been known to the outside world at least since the early first millennium BC. They are the direct descendants of the Aksumites (Munro-Hay, 1991). Wolbert Smidt (2012), a professor of Historical Anthropology, has noted: Tigray retains many ancient self-designations linked to the names of historical provinces. Etymologically, some can be linked to the Pre-Aksumite/Aksumite times. The people are the result of the process and interaction of Cushitic and Semitic people over the past thousands of years (Munro-Hay, 1991).

3. History of Territorial Reduction and Opposition

While Historic Tigray, albeit in different names and shapes, developed organically, as a project of the Tigrayans themselves, provincial Tigray was a victim of ‘de-Tigraying’ projects, through which successive Ethiopian rulers sought to disrupt the historical continuities of Tigray and its people by dividing up the entity along artificially imposed lines (e.g. Mereb Milash, Tekezze Milash, etc). Such delimitations were bifurcations of one people involving marginalization, linguistic assimilation, and strategic territorial reduction as a means of bolstering the center/s of the Ethiopian Empire.

Past Ethiopian rulers, for the reduction of historical Tigray territory and legacy, used foreign forces (e.g., Italy); likewise, today their political descendants invited multiple foreign forces (Eritrea, Somalia, et al.) for the same and more genocidal purpose.

The era of Provincial Tigray was an era of claim of territorial restoration and self determination for Tigrayans. As a result, these imposed borders, mainly in post-Emperor Yohannes IV (1872-1889) were opposed by Tigrayans. For instance Prince Ras Mengesha Seyoum (see interview: part i, ii, and iii) and Feteawrari Muez Beyene (see: interview) took issue with Tigray’s territorial reduction. Seyoum Maascio, an Eritrean opposition figure in 1947 against Emperor Hailesilasie´s rule, also identifies Tselemti, Welkait, and Tsegede as Tigrinya-speaking and affirmed his party’s intention to incorporate these territories as part of an attempt to create an independent Tigray-Tigrinya nation (see: letter of mahber Ertra n Ertrawian in the article). The letter recognizing the Tigrinya speakers’ history, language, and culture under subordination also resoundingly advocates for their restoration into their historic Tigray for self-determination. Gessese Ayele, who is more popularly known by his nom de guerre Suhul and who is a founding member of TPLF, Shire province’s representative in the imperial parliament of Emperor Haileselassie I (1930-1974), requested the same Emperor to restore Tigray’s historical borders: in the south (Aluweha: north of the town of Woldia) and in the west (Welkait) bordering with Sudan (see his letter on page 19). The 1978 political program of the TPLF also duly included Welkait Tsegede in the West and Alwuha-Milash in the South as parts of Tigray bordering Begemdir and Wollo respectively.

In the EPRDF era, Tigray though duly restructured as a member of the federal state, and constitutionally granted the right to self-determination, however, continued to be much smaller in size than the historic one. Tigray lost a massive land which later became part of the Afar region. Alwuha areas and several areas south of Welkait and Tselemti were never restored to Tigray.

Since the start of the war on Tigray in 2020, part of Southern Tigray, and Western Tigray were once again annexed to the Amhara Regional State by Amhara forces allying with the Ethiopian state and multiple foreign forces. In their attempt to make an ahistorical greater Amhara entity, the Amhara radicals still use ethnic cleansing and segregation as tools on populations who lived in mutual coexistence in these areas. This action has been coupled by exerted effort to change the demography of the areas, particularly in Welkait Tsegede. According to the census conducted by the Ethiopian Statistical Agency (see: census data) in 1994 and 2007 over 94% of the population were Tigrinya speaking people. Indeed, the underlying intention of the Triangular war on Tigray is the destruction of Tigray and the extermination of the Tigrayan people which human rights experts called genocide.

The archaeological and historical evidence linking modern-day Western Tigray to its historical roots and make-up is chronologically presented below.

4. Western Tigray in Pre-Aksumite Times

Ongoing archaeological research and findings indicate that the current Western Tigray including outlying areas up to Semien, Metema (መተመሕ፡ Metemeh in some historical sources), Lemalimo (Lemalmo: according to the 17th Barads`s naming), Emba Jewergis, Dabat (from Tigrinya Enda Abat), and Raesi Dejena was the primary resource base, home and corridor of the Pre-Aksumite polities and people of ancient Tigray.

4.1. Home

Myrrh, incense, and frankincense from Tigray have been exchanged throughout Northeast Africa and the Near East since antiquity (Getachew Nigus, 2022). Gerlach (2013:258) who studied Pre-Aksumite Archaeology mentions incense in Tigray has played a decisive role in establishing links with the eastern side of the Red sea. Western Tigray then was a territory with an extant of the incense species (see: current distribution map in the areas); it seems to have been the primary source of incense since the times of Punt and Da´amat. It is hard to trace incense itself from the archaeological records but incense burners, used perhaps during rituals, have been found in many Pre-Aksumite contexts (e.g. Adi Akaweh in Wukro) of Tigray.

The first evidence of the existence of elephants was found in Western Tigray at the rock shelter of Ba`ati Gaewa dated around the first millennium BC. Tekle Hagos (2019) documented that the art plausibly suggests the same animal existed around the Tekeze River since Pre-Aksumite times.

Many of the products known as Puntite exports are found in the ecosystem of Northwestern and Western Tigray. In fact, the Punt location is unidentified despite varied hypothetical propositions (see: Fisher, 2016: 3). Aksum (by Phillips, 1997), and Eastern Sudan (by Fattovich, 1991) have been proposed, while others propose outside the Northern Horn of Africa. Wherever the center of Punt might have been, this area probably was a quarry area of the same resources for Puntite polity and people.

4.2. Corridor

Archaeologists (e.g. Finneran, 2005: 7) have found evidence of cultural links between territories West of Aksum, and the Sudan steppes. For instance, obsidian resources were likely exported from the Northern Horn to Egypt around 4000 BC through trade routes located in the present-day Northwestern and Western Tigray areas (Hatke, 2013). Bard et.al., (2000) have also stated that Western Tigray has been a corridor for the movement of cattle from Sudan around 3000-2000 BC. A comparative study of lithic artifacts from the Gash Delta of Eastern Sudan and from Seglamen (near Aksum) (Laurel Phillipson, 2017) also support this finding. The presence of rock art sites in the pattern of Central Tigray (e.g. in Tembien), Northwestern Tigray (in shire areas), and Western Tigray (Ba´ati Gaewa in Tselemti) and the above evidence makes it the same part of Pre-Aksumite make-up and identity.

5. Western Tigray in Aksumite Period

5.1. Corridor

In the 1st millennium AD, Western Tigray continued to be a key corridor between the Aksumite polity and the Kushites/Nubians of Sudan (Hatke, 2013) and elsewhere. Internally, there are also recognizable ancient roads connecting e.g. Pre-Aksumite/Aksumite mai adrasha and Semema sites around Shire to Tekeze and the rest of Western Tigray. Nail Finneran (2005: 8) states even later in Medieval and Gonderine periods, since the establishment of Shire as center in the 14th century, there were still connections with Sudan in the west and Simien and North Gondar in the south.

5.2. Home

The territory up to outlying areas continued to be the home and prime sources of elephants, incense, sesame, myrrh, gold, and frankincense to the Aksumite polity of Historic Tigray.

Incense of Western Tigray continued to be a significant item in Aksumites too. It was known to be an alternative export item of the Aksumites. Shire Indasilasie remained a hub for frankincense production and processing in Northwestern/Western Tigray up to the 18th century (Getachew, 2022) and continues as source of incense to this time. This is the continuity and trend of the long-span Aksumite time. The 17th century Manoel Barradas mentions Tigray with a great abundance of sesame, which grows in the lands of Western Tigray which might have been also in Aksumite times.

It is mentioned that wild animals were hunted for ivory and rhinoceros horns during Aksumite times. The elephant population was one of the significant resources hence is chronologically discussed here. Historical evidence confirms elephants were certainly used for the transportation of heavy loads (e.g. Aksumite obelisks) and warfare by the Aksumites in the early first millennium AD (Tekle, 2019); their ivory was exported overseas. The statement from the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea gives two historical facts: western side of Tekeze as source of ivory as well as a home of Aksumite polity:

“ …From that place [Coloe: an inland town and marketplace for ivory along the Red Sea] to the city of the people called Auxumites there is a five days’ journey more; to that place all the ivory is brought from the country beyond the Nile [based on the distance calculation to mean Tekeze, not actual Nile see: Taddese Tamrat, 1972] …”

According to the observation accounts of Byzantine travelers of the 6th century AD, tusks of elephants were exported from the polity (see: Wolska-Conus, 1968). Taddese Tamrat (1972: 88) citing the 14th century hagiography of Aba Samuel of Walduba states that the valley of Tekeze River was very rich in elephants and kings were undertaking hunting of elephants, tusks of which they entrusted to their commercial agents during that time. It is also documented in the 18th-century travelers’ account (see: in Routes of Abyssinia: p. 253) that there were elephants across Tekeze areas. Melake Genet Gebre Cherqos Welde Aregay, who was a chief scribe in the court of Emperor Yohannes IV ( 1872-1889) in his narration recorded in Dimtsi Weyane Radio in 1985 “Tigray before hundred years“ also describes the abundant presence of an elephant found from Welkait to Metema; giraffes in Humera, Metema, and up to Atbara (of Tekeze) in the 19th century. Hence, Western Tigray has been the primary source, perhaps not the only one, of elephants for the Aksumite polity. .

An ethnographic study which included field observation on gold mining tradition in Tigray is conducted by Smidth and Gebremichael Nguse (2012). Documenting many gold mining and panning sites, it concluded that gold mining is a traditional practice in Tigary. In fact, Aksumites had gold coinage: export and local use; 16th century Francisco Alvares account also mentions he was told people in “Tegré Mekonen“ or kingdom had bountiful gold resources; he himself participated in the panning. The same study remarked that some of the local gold mines follow an ancient pattern. There are sites named e.g. Adi Werki (gold mining site) in Welkait. I hypothesize that probably Western Tigray had been one of the primary sources of gold for the Aksumite polity and people.

The Kunama ethnic group is found in Northwestern and Western Tigray: Adabay, Adameyti, Adi Goshu, and to some degree in Kafta Humera. The earliest written mention about the Kunama´s presence in Eritrea, Ethiopia (particularly Northwestern and Western Tigray), and parts of Sudan was by the 9th and 10th century Arab travelers: Al-Ya’qubi the 9th century historian and Ibn Hawqal the 10th century geographer (Tadesse Tamrat, 1972). Narration from the group itself as per the interview from elders in Sheraro and Humera (see: Andualem Tariku: 2019: 1048-1050) highlight that their history is associated with Aksumite King Baden/Bazen (and his wife Kuname) who ruled Aksum in the transition from before the Birth of Christ (BC) to Anno Domini (AD). Hence, the Kunamas are one of the indigenous Tigrayans to Western Tigray since Pre- and Aksumite times.

6. Simien, Lemalmo, and Metema Borders of Historic Tigray

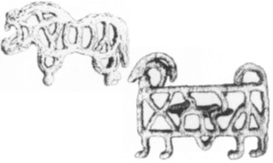

As chronologically discussed in the above sections, the home and resource base of the ancient polities extends up to outlying areas of EPRDFs Western Tigray. Toponyms of mountains, rivers, and villages in these already Amharaized areas have intact Tigrinya names. The presence of Walia Ibex across Pre-Aksumite Tigray is informative that the areas were domains of the polity. They are represented in the rock arts, particularly, in rock paintings of pre-Aksumite time in central and northwestern/western Tigray and as figurines, freezes, and royal seals mostly found in Yeha, the epicenter of the Damat polity. As Finneran (2007) and Manzo (2009) state, Ibex seems to have been associated with sacred value animals, the reason perhaps why they are found in many places across ancient Tigray. They are now found in Simien mountains which was the frontier of Aksumite polity.

Geographic and historical reports on Western Tigray and its outlying areas as an integral part of Historic Tigray are corroborated by ancient inscriptions of the Aksumite kings. King Ezana’s inscription from the 4th century and the stone inscription in Aksum attributed to King Ella Amida mention that the inhabitants of Simien were paying tributes to the Aksumite kings. Furthermore, the Aksumite inscription from Adulis known from the report by Cosmas Indicopleustes’ book Christian Topography mentions a mountain covered with snow (snow-covered), (see: Phillipson, 2012). As a traveler he came with an itinerary to visit and did visit Aksum capital and its domains too (Simien). Historical evidence indicates that this mountain was either the mountain chains of Lemalmo or Mt. Ras Dashen, i.e, the highest peak in the territory. Lemalmo, and Semen or Simien are mentioned by a Jesuit Missionary from Portugal, Emanuel Baradas, as the borders of Tigray in the early 17th century. The linguistic evidence in the preamble of versi abissini (ቅኔ፡ሓበሻ) by Jacques Faitlovich (1910) “Tigrinya had been in use in a large part of Semien and in the whole of the Tselemti province up to the Dibba-Baher district, at the foot of the Lemalmon pass that forms its border to Wogara“ also confirms.

The Metema area has been part of the western territory, a resource base and home of the Pre-Aksumite and Aksumite polities and people of ancient Tigray. Michel Russel (1833) also mentions Tigray was bordered by the Shankila people (a pejorative term for darker skinned ethnic groups) in the West. That is referring to the Gumuz ethnic group in the current Benishangul Gumuz region which is bordered by Metema.

7. Welkait, Province of Historic Tigray

To the dismay of the counterarguments flowing from the Amhara´s expansionist camp based on fictitious claims, toponymic, linguistic, and historical evidence of Welkait (ወልቃይት or ወልቃኢት- in some sources) and its surroundings speaks for itself.

7.1. Administrative History

Aksumite´s Hatsani Daniel mentions a toponym WYLQ possibly Welkait from Western Tigray (Phillipson, 2012:77). David W. Phillipson refers to the toponym Welkait, the area southwest of Aksum and beyond the northward bend of the Tekeze. The inscription is paleo-graphically dated to the 8th/9th century AD, a time when the emperor was weak but people (ሰብኣ-Säb’a) in provinces (like Welkait) were still under local chiefs. If the toponymic interpretation is correct, that is if WYLQ= Welkait, it is one of the pieces of evidence that Welkait was under the Aksumite polity.

After the fall of the Damat Kingdom (400 BC), there was a period with no mighty emperor and it was after this gap local rulers with respective petty polities formed (100 BC/100 AD) another mighty polity centered at Aksum (Fattovich and Bard, 2001:4). Hence, Aksumite polity was a formation of rulers of provinces who worked for the state (Munro-Hay, 1991). The mention of Säb’a Welkait (ሰብኣ-ወልቃይት) is analogous to and parallel with Säb’a Enterta or Enderta (Enderta or Enterta People), Säb’a Agame (Agame People), Säb’a Azebo (Azebo People), Säb’a Womberta (Womberta People), and Säb’a Segli (Segli People), Säb’a Wejjerat (Wejjerat people) and the like we see in historical sources. It is an exact reference defining people (Säb’a) in a certain domain (Welkait) under the polity (Aksumite identity).

The mention of the walduba monastery as second of the five main religious sanctuaries in Tigray ``never molested by the troubles and horrors of Abyssinian war-Axum, Waldeba, Gunda Gundi, Debre Damo, Debre Abay“ in the book “Abyssinia and its People, or Life in the land of Prester John” in 1868 (see: page 13) confirms two facts: administrative history and identity.

7.2. Identity and Linguistic History

James Bruce`s 18th century manuscript named as “MS Bruce 94“ states Welkait and its surrounding had Tigrinya-speaking Bete Israelite inhabitants: “in regions to the north and east of Gondär, namely Wälqayǝt, Ṭsägäde, Ṭsällämti, and Wag Hǝmra they [Bete Israel people] spoke Tigrinya…“(Dege-Müller: 2020: 14). There are also Tigrinya names of flat-topped areas (Emba Redaè, Emba Falasha, Amba Adi Ero) where the Tigrayan Jewish lived according to 19th and early 20th-century European travelers (see: Abbink, 1990: 444). The Tigrayan Bete Israelites associate their history to the history of the Ark of the Covenant, Pre-Aksumite times. There is the same community in Northwestern Tigray.

The recent Jan Nyssen´s work on history of Western Tigray from 108 historical and 21 ethno-linguistic maps (1607-2009) shows the Tigrinya composition of the last 400 years. This shows the fully eternal Tigrinya character” of Welkait and the surrounding districts during its entire history.

A total of 575 toponyms, out of which 229 names prefixed with “addi” (meaning village, place, home of), 49 names prefixed with “may“ (meaning water, spring in Tigrinya) extracted from the ethnographic work of Giovanni Ellero, an Italian administrator of Welkait during the Italian occupation in the 1930s show that all the toponyms in Western Tigray are derived from the Tigrinya language (Nyssen, 2022). Many of the names: Wollel, Zana, Tsana, Tabir, Medebai Tabor, etc are even identical to names known as Aksumite sites in Aksum and elsewhere. To add an example, Mai Guba (Aksumite name), a place name in Welkait, known in historical records is identical to the toponyms of Mai Guba, Endaba Guba and Abune Guba in the rest of Tigray. Abune Guba is the name of one of the Nine Saints who came from various parts of the Roman Empire to Aksum in the late 5th century AD for evangelization and expanded monasticism in Tigray. Whether there is an Aksumite establishment or a site attributed to the saint in the area needs further archaeological study.

Apart from archaeological and historical sources, the church’s mounting evidence specifically describes the Tigrayannes of Western Tigray in general and Welkait in particular. The monastery of Aba Samuel Walduba in Welkait which was founded by a Tigrayan monk by the name Aba Samuel from Aksum in the 14th century is another case in point. Oral tradition pushes the date of establishment as a religious place back to the middle Aksumite times, 490 AD, but needs further study. The mention of the monastery as second of the five main religious sanctuaries in Tigray in the book “Abyssinia and its People, or Life in the land of Prester John” in 1868 (see: page 13) supports its Tigrayan/Aksumite identity. The monastery is contemporary with and sibling of many churches and monasteries in other parts of post-Aksumite and medieval Tigray. It is believed that it has a strong link with Debre Bonkol monastery of Aksum, which was believed to be a place of Bahre Negasi of the 13th century.

A preamble of versi abissini (ቅኔ፡ ሓበሻ) by Jacques Faitlovich (1910) stating historically, Tigrigna used to dominate a larger territory, than its map in EPRDF´s Tigray, in Lasta, Zebul, Yejiu, and Eastern Danakil areas, current Western Tigray and its outlying areas:

“Tigrigna, Tigrinya or Tigrai, a language spoken…throughout the entire northern part of the Negus empire, on this side of the Tekazzé and on the other side of this river in the western provinces, in Tsegdie, Wolqaït, Waldebba and in a part of Tselemt. “

Even toponyms of mountains, rivers, and villages in the already Amharaized north of Gondar (outlying areas of Western Tigray) have intact ancient Tigrinya toponyms while some toponyms through the assimilation and phonological process added another, or Amharic, forms. According to the ethnographer Giovanni Ellero, an Italian administrator during the Italian occupation in the 1930s, “in all villages (under Welkait administration), the people were reported to speak Tigrinya, with mostly passive knowledge of Amharic. Those who were literate wrote in Amharic; Ellero mentions that all communication with the administration was in Amharic“ (Nyssen, 2022: 2).

Being part of Tigray in Pre-Aksumite, Aksumite, and post Aksumite times as well as in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries (see: historical cartography by Nyssen) confirm that Welkait in administration and identity has historically been Tigray. But the serious impact of the continuous assimilation, language prohibition, cultural predation, administrative pressure, and economic untying and dismantling of Welkait and its other districts from the rest of Tigray on the linguistic and identity composition can not be undermined.

8. Tekeze, River of Tigrayan Polities and People

8.1. (Re)Source of the Civilizations

Ancient literary evidence, including the book of Aksum mention numerous toponyms of Tigray. Tekeze (the name by which the Aksumites sometimes called the river strentching from their territory (the current Tekeze) to Egypt) is one of the prominently known geographic features in the Horn of Africa, and is mentioned in ancient inscriptions. Some, e.g. Marrassini, (2014:232) identified the mention of the Tekeze river in the Ezana inscription with the Atbara River (the lower course of Tekeze in Sudan). The river and its banks being within the domains of the polities was significant.

Rivers are considered the most important geographical feature of ancient civilizations; rivers give the inhabitants a reliable source of water for drinking and agriculture. For example, the Egyptian civilization had the Nile River and its valley. It is not surprising that settlements were often found along rivers and valleys; similarly, Tekeze contributed to the emergence of settlements and the development of ancient Tigrayan polities. The presence of rock art sites in Mai Lemin Gebriel and Bea´ati Gae’wa and other settlement sites located across the Tekeze banks of the river shows the ancient significance of the river. Thematically, the arts portray wild and domestic animals and significantly the domestication of animals. Given the fertile nature of the area with the river and tributaries, it may have played a big role in the domestication of animals.

A groundbreaking discovery, the newly discovered archaeological site of Ketema Ra’isi, located close to the bank of the Tekeze River, is potentially informative for the western side of the Aksumite capital, Aksum. The findings are Christian Aksumite coins of the 4th century which confirm it as the core territory of Aksumite polity. The discoverer of the site mentions it as a promising site, stating “it will provide an archaeological link between the central-western Tigray and the southern lands of Sudan.“ see: P. 463.

Tekeze River being part of the western corridor was important to direct routes and contacts. Archaeologists reconstructed (see: Phillips, 1997: 440-441) that the main overland route from the western side of the Red Sea, through Aksum was probably through or near the Gash and Atbara (lower course of Tekeze) rivers to Nile River. For instance, the Kebra Nagast, which took on its current form in the 13th century, claims that legendary Menelik I returned to Ethiopia following the route of the river. This indicates that the Tekezé River served as an early link between Ethiopia and Egypt via Sudan.

8.2. Tekeze: the Fictitious Border of the Fictitious Narrative

Tekeze has been used as a toponymic reference within the ancient polities domains due to its prominence. This made the river known to Europeans visiting Ethiopia in the last century or so; they perceived or were told the river was as a rough border. Moreover, their reference to the river was neither history nor identity and linguistic composition but the contemporary administrative rule of modern center Begemdir/Gonder vs provincial Tigray. In fact, Ethiopian rulers centered in their parish, sometimes after military fortunes, other times as a way to reward their royals in Amhara, but all to reduce Tigray used it as a border for rule by completely disregarding millennial historical continuity and the people’s identity.

People on both sides of the river call it Ruba Tekeze (meaning Tekeze River), and its tributaries are also Rubatat (rivers), hence are associated names in Welkait, e.g. Ruba Lemin. Historically, they don´t use tekeze as a delimitation or reference; if there is any, it is analogous to the use of Weri milash/leke, a tributary of tekeze in Tigray, which is not an identity delimiter but a geographic reference.

9. Conclusion

The history of provincial Tigray has a history of territorial decimation along with language destruction, which caused demographic changes and ultimately the shrinking of the Tigrinya map. The Western Tigray in question is a constitutional one but historically is beyond the constitution´s domain. Despite the imposed lines and layers by recent imperial rulers, Western Tigray history falls within Tigray. The historical evidence and archaeological makeup showing cultural, historical, linguistic, and anthropological continuities and patterns in Northwestern/Western Tigray clearly nullify the fictitious attempt to disconnect Western Tigray from the rest of Tigray.

Western Tigray is not a modern claim but a link to a continuous history spanning millennia for Tigray. In Western Tigray, memory, history, heritage, territory, and people are inextricably linked, as well as by-products of the long-span civilization. Hence, its people are Agazians, Aksumites, and finally Tigrayans in their identity and are autochthonous to their territory.

In addition to the illegal and deceptive nature of Amhara claims, there is no archaeological data or historical evidence from the Amhara´s expansionist camp except for their intention to destroy the legacy and cohesion of Tigray’s territory and nationhood.

Negasi Awetehey is a lecturer at Aksum University's Department of Archaeology and Heritage Management. Currently, he is doing his masters study in the Erasmus Mundus program of Archaeology and Pre-history in Portugal.

Geatcho

April 16, 2023 at 5:18 am

Thank you so much for this article with such great detail and clarification!

Solomon Brhane Asfaw

April 10, 2023 at 1:19 am

absolutely true expression.

Tsegazeab Mezgebe

April 4, 2023 at 7:32 pm

You nail out the truth my friend and colleague Negasi and I thank you very much for your dedication.

ማህበረቅዱሳን የሌባ ቀማኛ ዘራፊ ማፍያ አሸባሪዎች ጥርቅምቃሚ ዘኬ ቃራሚ

April 4, 2023 at 10:27 am

ማህበረቅዱሳን የሌባ ቀማኛ ዘራፊ ማፍያ አሸባሪዎች ጥርቅምቃሚ ዘኬ ቃራሚ

ሙዳዬ ምጥዋት ገልባጭ

Fano and all amhara socalled special killing squad enganged in robbery and sexual assualt crimes against nuns and massacring priests should be disarmed and dismantled instantly without delay , agreed the the most respected Ethiopian parliament members this morning.

መነኩሴ እና የአምስት ዓመት ህፃን ደፋሪ አሣፋሪ ብሔር አማራ ብሔረ ፉከራ ታሪክ አልባ ለቅጠል ኮሽታ የሚሆን ደምባራ የሰው ልፋጭ እንጭጭ ሂማን ዌስት

No more working with genocidal church of Amhara in Ethiopia

April 6, 2023 at 4:34 pm

The decision to merge the Menbere Selama Kesate Birhan Orthodox Tewahedo church of Tigray with any oriental church is not only limited to the archbishops of Tigray but also the entire membership of the church, all laity of the Tigray Orthodox Tewahedo church. Nearly all the people of Tigray don’t want to join the Amhara church in Ethiopia. The TPLF has no right to decide the fate of the Tigrayan Orthodox Church and can’t force or even persuade Archbishops to mix with the genocidal church of Amhara, which has already sent a letter to politicians in Tigray to help them put pressure on religious leaders in Tigray.

Anyone like Nibure-Ed Elias ( (የልዩ ጽ/ቤት ኃላፊው ንቡረዕድ ኤልያስ አብርሃ ) who is working with the Amhara Orthodox church in Arat Kilo to dismantle the Menbere Selama Kesate Birhane Orthodox Tewahedo church of Tigray must not be allowed to enter Tigrayan soil. Banda(traitors) who support the genocidal church of Amhara are also genociders!

ማህበረቅዱሳን የሌባ ቀማኛ ዘራፊ ማፍያ አሸባሪዎች ጥርቅምቃሚ ዘኬ ቃራሚ

April 4, 2023 at 10:26 am

ማህበረቅዱሳን የሌባ ቀማኛ ዘራፊ ማፍያ አሸባሪዎች ጥርቅምቃሚ ዘኬ ቃራሚ

ሙዳዬ ምጥዋት ገልባጭ

Fano and all amhara socalled special killing squad enganged in robbery and sexual assualt crimes against nuns and massacring priests should be disarmed and dismantled instantly without delay , agreed the the most respected Ethiopian parliament members this morning.

መነኩሴ እና የአምስት ዓመት ህፃን ደፋሪ አሣፋሪ ብሔር አማራ ብሔረ ፉከራ ታሪክ አልባ ለቅጠል ኮሽታ የሚሆን ደምባራ የሰው ልፋጭ እንጭጭ ሂማን ዌስት

Belai Tedla

March 31, 2023 at 11:36 am

Professional way of presentation.

The contents are factual proved by historical facts.

Many thanks for your dedication to reveal the truth.

Hiyab

March 29, 2023 at 12:31 am

Thank you Mr. Negasi. It is a very great article that everyone should read, learn from and dispatche.

Kiros

March 28, 2023 at 3:06 pm

Interesting and non doutful.